In a hydrogen bond X–H···A, the group X–H is called the donor and A, which has a lone pair of electrons, is called the acceptor (short for "hydrogen donor" and "hydrogen acceptor", respectively). The X–H σ bond of the donor points at the basic lone pair of the acceptor (:A). Most hydrogen bonds look like O–H···A or N–H···A, where A is nitrogen or oxygen. [Note: "–" and "···" correspond to covalent and hydrogen bonds, respectively.] The type of hydrogen bond that accounts for the majority of those in proteins and nucleic acids is the hydrogen bond between the sp2 on a carbonyl oxygen as an acceptor and the N–H bond.

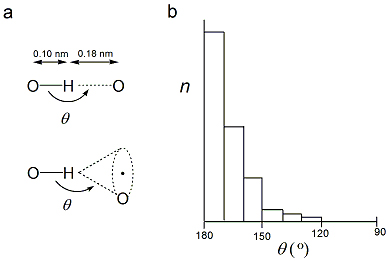

The hydrogen bond is directional but flexible. The total interaction in a hydrogen bond is dominantly electrostatic, which leads to pronounced flexibility in the bond length and angle. The distance between X and H, when X is either nitrogen or oxygen, is 0.10 nm or 1.0 Å (Fig. 1A). The hydrogen bond is much longer (about 0.18 nm) and weaker (about 1/30th) than the covalent O–H or N–H bond. In contrast to σ covalent bonds, lengths and angles for hydrogen bonds are not fixed precisely (see below). Nonetheless, the hydrogen bond is the most directional of noncovalent interactions.

Figure 1: Geometry of the Hydrogen Bond

a) The length of a hydrogen bond is simply the distance between the hydrogen atom of the donor and the acceptor atom. [Note: In the past the length of the hydrogen bond was the distance between the two heavy atoms because the position of the proton in the hydrogen atom is difficult to determine.]

(b) Distribution of values for the angle θ for hydrogen bonds in high-resolution crystallographic structures of proteins and nucleic acids. The angle θ is the angle between the hydrogen bond and the covalent σ bond.

Strength of Hydrogen Bonds

What we commonly call the "strength" of a hydrogen bond depends not only on the chemical donor-acceptor combination, but also on the bond lengths and bond angles. In a given set of hydrogen bonds, the strongest hydrogen bonds are those closest to perfect geometry.

The schematic energy diagram in Fig. 2 shows that a stabilizing interaction (that is, with E < 0) is associated with a repulsive force if d is shorter than the equilibrium distance d0. At longer distances, the hydrogen bond energy is dominated by the electrostatic energy term, which decreases slowly with distance. It is customary to classify hydrogen bonds as "weak", "strong", and "normal". Strong hydrogen bonds have bond angles close between 170 and 180 degrees. Weak hydrogen bonds have bond angles less than 120° and bond lengths greater than 0.22 nm. At these distances, the van der Waals interaction may contribute as much as electrostatics to the total bond energy. The main structural feature distinguishing a weak hydrogen bond from the van der Waals interaction is the preference for alignment of the donor with the lone pair orbital of the acceptor.

Figure 2: Typical Hydrogen Bond Potential