You are using a web browser that is not fully supported by this website. Some features may not work as intended. For the best experience, please use one of the recommended browsers.

Opening Image: tRNAGlu complexed with glutamyl-tRNA synthetase. The three nucleotides of the anticodon are spacefilled.

Because of its importance in protein synthesis, its small size, and its availability, tRNA became a favorite example of a nucleic acid molecule in the 1960s. The first determination of the primary structure of a tRNA by Robert Holley's group in 1965 earned him the 1968 Nobel Prize for Physiology. The publication in 1974 of the crystal structure of yeast tRNAPhe was the first, and until recently, the only 3D structure of a natural intact nucleic acid. It provided a picture of the ordered complexity of a folded RNA molecule. Among the many features was the first picture of a G·U base pair in a double-helical stem in which the hydrogen bonding was that predicted by Crick's "wobble" hypothesis.

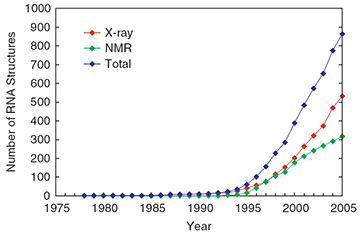

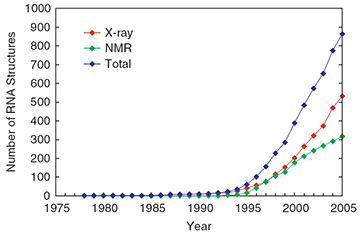

Since 1974, the number of resolved tRNA structures has increased greatly: see .

RNA secondary structure is defined by which bases are paired in the molecule. Secondary structure diagrams are generated automatically by computational methods based on alignment of multiple sequences or on algorithms which search for the lowest free energy. Some programs combine these concepts.

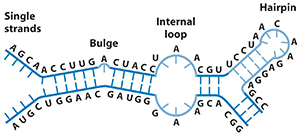

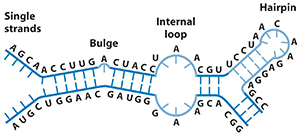

RNA secondary structure is generally divided into stems (helices) and various kinds of loops (unpaired nucleotides surrounded by helices). The stem-loop or hairpin structure, where a helix ends in a short loop, is extremely common and is a building block for larger structural motifs, such as the cloverleaf structure found in tRNAs. Internal loops (a short series of unpaired bases within a longer double helix) and bulges (regions in which one strand of a helix has "extra" bases in one strand with no hydrogen-bonded partner in the opposite strand) are also frequent ().

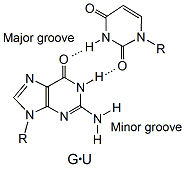

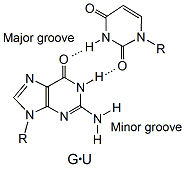

The G·U wobble base pair (see ) is an essential element in RNA secondary structure. It is nearly isosteric to the Watson-Crick base pairs, G·C and A·U, and therefore often substitutes for them. However, the G·U wobble base pair has unique chemical properties, which can only be partially mimicked by Watson-Crick base pairs and which allow the wobble pair to play essential functional roles in a wide range of biological processes.

tRNAs are fundamental actors in the conversion of the 4-letter nucleotide alphabet into the 20-letter protein language. tRNAs are responsible for the actual physical matching of each codon in a mRNA with the anticodon, three bases that are complementary to the codon.

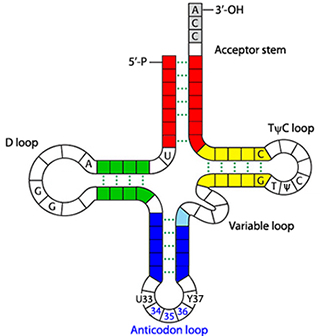

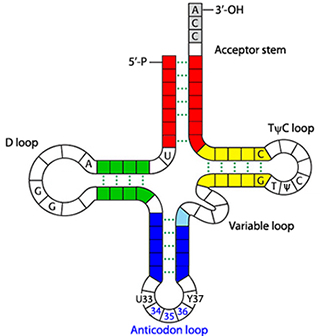

tRNAs have a cloverleaf-like secondary structure and an L-shaped tertiary structure. The cloverleaf has well-defined characteristics, including size of stems and loops (). The L-shaped tertiary structure is based on an intricate and precise network of non-covalent interactions. Each tRNA has four double-helical stems and an invariant CCA amino acid attachment site at its 3′ end.

Nucleoside modifications are critical both for structure and function. For example, a number of pathogenic mutations in human tRNA genes are linked to modification defects. For example, methylation of A9 in tRNALys disrupts a Watson-Crick base pair but is important because without the methyl group on N1 of A9 the tRNA folds incorrectly and loses function.

All tRNA molecules are L-shaped, except for several mitochondrial tRNAs.

Van der Waals surface of yeast tRNAPhe.

space-filling model. The sugar-phosphate backbone is shown in CPK colors.

of the bases. Colors for the double helical stems are the same as in the cloverleaf diagram ().

the atoms corresponding to the temperature factor. The anticodon loop is more dynamic than the rest of molecule, except for residues at the 5′ and 3′ ends. The "coolest" regions are associated with the D loop and the TψC loop.

backbone trace. Phosphorous atoms are shown in spacefill.

One of the outstanding features of tRNA is the fact that most of the bases are involved in base stacking.

out of 76 bases are stacked.

All three nucleotides, G34-A35-A36, of the are stacked on each other.

All tRNAs from archea to eukaryotes have an invariant G·U in the acceptor stem. The wobble pair is essential for acylation of the tRNA by amino-acyl tRNA synthetase, which forms a complex with tRNA, ATP, and a cognate amino acid to catalyze transfer of activated amino acid to the 3′ end of the tRNA.

model of the solvent-accessible surface. The wobble pair is shown in spacefill with CPK colors.

Juxtaposition of the G·U wobble pair of tRNAGlu against glutamyl-tRNA synthetase.

to yeast tRNAPhe.

form a non-standard base pair.

out of 76 nucleotides contain post-translational modifications.

is a modified guanine.

The between 2-methyl-G26 and A44. What effect does the group, have on the geometry of this base pair? How many hydrogen bonds are there between the two bases? Are they weak or strong hydrogen bonds?

Tertiary base-base hydrogen-bonding interactions involve one, two, or three hydrogen bonds between the edge of a Watson-Crick base pair and a third base, which is enclosed in parentheses. As expected, all three bases lie in a plane. There are three base triples in the yeast tRNAPhe.

all three base triples.

Tertiary structure defines the shape of a molecule. In an RNA molecule that folds into a unique three-dimensional structure, the tertiary interactions between different secondary structural elements make a significant contribution to the stability.

spacefill. by temerature factor.

Before we bid farewell to a fascinating molecule, remember that an RNA structure is not static. tRNA must interact with many other components of the protein synthesizing machinery and it does so by changing conformations.